Okay actually it’s not. And I’m not going to be talking about life either. Actually I’m going to talk about structure! And adaptations!

I’ve loved fairy tales for a long time. We had a Random House compilation of fairy tales along with various picture book iterations of many of them and while sometimes I’d just sit and absorb the beautiful illustrations, sometimes I enjoyed comparing the various versions of the stories.

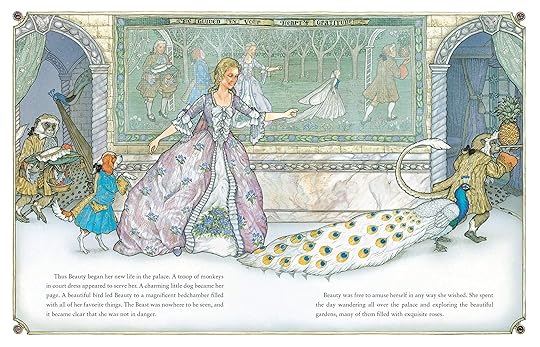

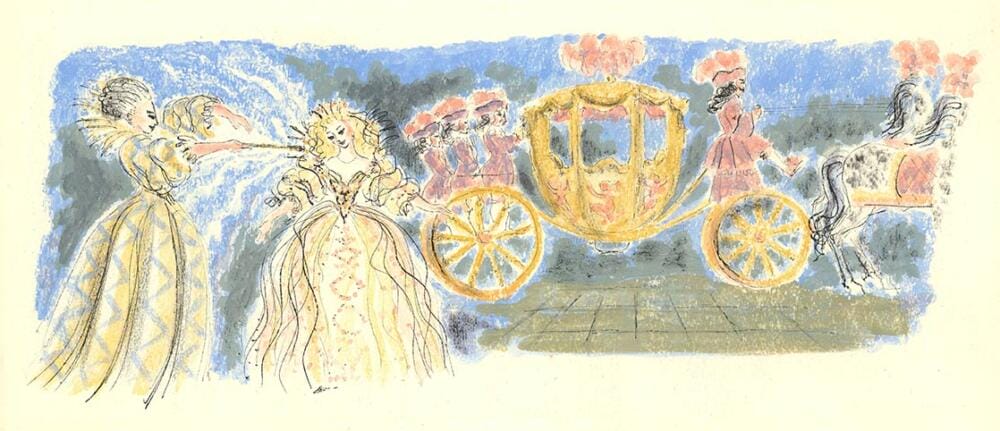

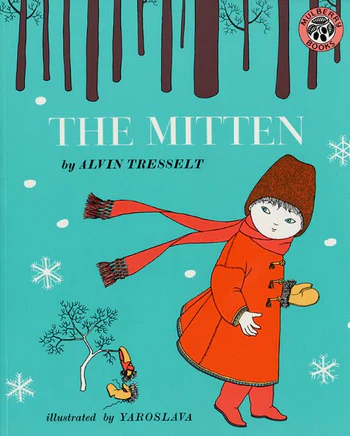

I mean, just look at these. Such different styles but all beautiful in their own way.

And of course, retellings of fairy tales are a genre all to themselves. Ella Enchanted and Fairest and many others by Gail Carson Levine, Beauty and Spindle’s End and a whole host by Robin McKinley, Marissa Meyers’ The Lunar Chronicles, Orson Scott Card’s Enchanted, and truly so many others that I’m going to stop before this becomes about where to find retellings.

But why are they so popular? I figured that out pretty fast for my own purposes; one of the first novels that I thought was actually pretty good and maybe even share-able (please don’t hold my high school novels against me) was based on a Russian/Ukranian folk tale The Feather of Finist the Falcon (among many other titles, as folk tales do). One of the appeals for me is that it gave me a different puzzle than writing a book from whole cloth.

When you start from scratch, you have to create a whole story. Characters, plot, motivations, setting, everything. There is a new world that belongs only to you (until you share it). In essence, you’re creating a table by starting with a log. But with a retelling, fairy tale or otherwise, it’s a different puzzle. You’ve been given characters and a plot but for the most part, the motivations, setting, character interaction, and so forth, are on you to not only decide but to make work within the framework of the story. What parts fit? What parts don’t? What can you tweak to make this make sense? How does this fit in the world you’re creating? To continue the earlier metaphor, you’ve been given access to a workshop crammed with random bits of wood and you need to make a table out of that. It’s not easier, necessarily, but it is a different puzzle working with different skills.

Because it does take different skills, it can actually be a good exercise. Also, depending on where you go with it, such a story can take very different turns. I have two major divisions in that; retelling vs. based on. In those categories, retellings are stories that hold pretty true to the basic beats of the original story.

Beauty, for example, is a retelling of Beauty and the Beast. The main beats of “girl offers herself as prisoner in a castle to pay for father’s mistake; the girl gradually comes to care about her captor and see beneath his beastly exterior to the caring heart within,” kidnapping notwithstanding,1 are all there. Or Cinder; the unacknowledged girl with the heart of gold is discovered by the prince because of her footwear fitting her alone. But the two of those in contrast show how far you can go within the bounds of retelling. Beauty sets the story in a fairly typical quasi-European country, taking the “dad was a merchant whose wealth got lost” version and embellishing it up. Basically it’s the Jan Brett version I read as a child but expanded into a story, which gives us time to dwell on the characters, the situation, where the appeal for each came from, and so forth. Growing a tree from a seed, so to speak. Where with Cinder, Marissa Meyer made a very unfamiliar fairy-tale setting and transposed it to a cyber dystopia. Cinderella is not a scullerymaid but a mechanic, though she does live with a stepmother. She doesn’t lose a shoe but a whole cybernetic leg. And the expansion to a novel allows for not only building up the character but creating a world and plot beyond, to the point that the discovery of her true identity is really only a cliffhanger for the series.2 In this instance and returning to the metaphor, creating a metal sculpture of a tree. Recognizable but entirely different materials.

Retellings work so well, in my opinion, because a fairy tale is little more than a skeleton on which to hang a story. Generally the person with the most character development, if you’re lucky, is the main character, who gets to be clever or sweet or even just a little simple-minded and innocent and lucky. Everyone else? Their motives are inscrutable, their methods opaque, and therefore a blank canvas on which to make whatever you want. And hey, nothing’s stopping you from changing that main character up either. I wrote a Beauty and the Beast story in my youth that had Beauty being utterly beastly and the beast3 being stuck with her due to the curse. As long as it’s recognizable, you can pitch it with “It’s The Twelve Dancing Princesses but they turn into marionettes at night” or “It’s Jack and the Beanstalk but Jack is a dwarf and the beanstalk is a mine rope” or “It’s Snow White but she was replaced by a changeling at birth which is why she’s so beautiful but only her stepmother notices something’s wrong.” (Free ideas if anyone wants them.)

The other version is “based on” or “inspired by.” Books that fit in this category are things that take the feel of a fairy tale and run with that, making their own thing. For example, pretty much anything written by Diana Wynne Jones but especially Howl’s Moving Castle or The Dark Lord of Derkholm. They take the feel of fairy tales, such as the magic of three things, the traveler doing favors and receiving gifts that help them later, the youngest child being the one with the good luck, and similar tropes, to build a world that we feel familiar in.

And that, there, is the key to why I think people keep coming back to retellings, both as authors and as readers. There’s a theory often referenced on the podcast Writing Excuses and other places that the way to bring in an audience is to create something familiar yet different. When looking for a story to experience, people want different amounts of overlap of the familiar and the novel and putting a story in the context of a fairy tale grants instant familiarity to draw in readers. But that’s enough for this round, I’ll talk more about familiar and strange next week.

Intellectual Property of Elizabeth Doman

Feel free to share via link

Do not copy to other websites or skim for AI training

- Ok so apparently Stockholm Syndrome isn’t actually what popular media says it is; it was developed off of an incident in, surprise, Stockholm. Discussion here: https://youtu.be/p54tpokHrpo?si=m-V0FcRmlFQXwIMv&t=1148 . I saw a more in-depth discussion somewhere recently, probably also on this channel. ↩︎

- This was my least favorite part of the novel; I read it for the first time somewhere between 8th and 10th grades, can’t remember which, and immediately pegged that [spoiler] Cinder is the lost Lunar princess [/spoiler] in the first chapter and waited the entire rest of the book for that reveal, frustrated each time it didn’t happen. I read the rest of the series though, so I guess it worked anyway.

↩︎ - In this version a griffin; I felt very clever as I populated the castle with various cat/bird hybrids. My favorites were her lady’s maid who was a snow leopard/snowy owl and the only one who could communicate with people, an African gray parrot/tabby cat. ↩︎