So last week I promised a post on the familiar and the strange. I could just go to the Writing Excuses website, find the relevant episodes, and link them here, but I’m going to let you take that adventure and instead regurgitate and rewrite it as I remember and understand it.

First off, what’s this all about? Well, this is essentially about what an audience is looking for in a book. Here’s the thing; this is a tool to help you create a book but not a foolproof “make people love it” guide because different audiences want different things. So if you make something to attract audience A, audience B is still going to leave neutral or bad feedback because they were looking for something else. And audience C is going to utterly hate it.

Back to the question: what’s this all about? When people read a book, they’re looking for something, some escape or adventure or vicarious experience. And when they pick up a new book, they’re looking for some amount of novelty. Otherwise they’d read the same five books over and over. However, if you give something completely new, they’re not going to have a stable foundation to stand on while they understand the new world of the story. Also, they’re looking for a certain experience they already understand. Let’s break it down more.

What is the “Familiar?” It’s things an audience is already comfortable with. Maybe it’s plot structure like underdog sports story or Beauty and the Beast style romance. Maybe it’s set in the modern world so characters are familiar with it or set in the vague European pseudo-middle-ages that a lot of fantasies end up in with castles and forests and knights and wizards. You give someone (in the Anglo-European-centric world) that image and they’re in already. Maybe it’s the type of character; the evil suave vampire, the white-hatted noble cowboy, the beautiful and strong princess, the rogue with a heart of gold, those types of strong archetypes. I wouldn’t say all the above in one story but that would be an interesting challenge. (In fact, that would certainly add a lot of “strange” to the story already.) So familiar = things the audience already is familiar with. Not too hard.

What’s the “Strange” then? Those are things the audience hasn’t encountered before. Reasons to read this story instead of something else. Ways this story is set apart. For example, putting a cowboy and a vampire and a princess in the same story. Or making Cinderella into a cyborg in a cyber-dystopia. Or throwing Jason and the Argonauts into space. (Mine, my idea, you can’t have that one. :D) Or telling it from a different point of view. Maybe you tell the entire story in epistolary format. I did one that was all overhead announcements in a store once. Maybe it’s second-person point of view, like If You Give a Mouse a Cookie. Maybe the strange part of your story is that none of the characters are human.

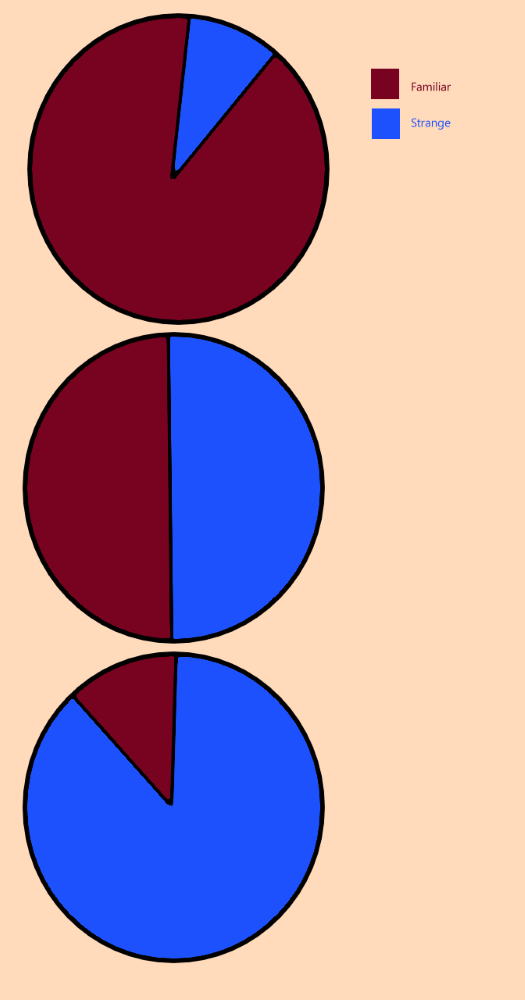

Hopefully that gives a decent understanding of the difference between the familiar and the strange. Now we come to how to blend them. I made a graphic for this but it’s mostly for reference, the methods are pretty easy to understand.

The three basic blends are simple:

-Mostly familiar

-A good blend of both

-Mostly strange

The big difference between these is going to be the audience you’re trying to engage. Certain audiences want the story to go along expected lines. For example, the romance genre has a lot of books that follow the same basic plot structure, beat for beat, with just a few things changed around. That’s even a selling point of many of the romance books; if you browse for them, you’ll find them labeled by the type of story you can find within. The audience for these books are mostly people who are seeking a comfort read. They want to know what they’re getting in to, they want to already know how the book is going to make them feel, and that this book will exactly hit the mood. My analogy for this is having a substitute teacher. School proceeds as normal, but the day is just a bit different than you’re used to.

Then there’s a pretty consistent blend of the familiar and the strange. That’s where I’d put a lot of the stories I read and write. There’s a lot of new things, like new aliens or new magic or new twists on familiar stories. The hardest part with this is introducing the new things in a manner that helps the reader learn them without becoming overwhelmed. Or without the writer being overwhelmed– my current struggle in Astronautica. (Have you seen how many people go on that ship? And I’ve pared it down! A lot!) This might be more comparable to seeing your teacher outside of school. Two big elements, the characters involved, are the same, the surrounding circumstances are familiar to you, but the joining together of these in a new way makes it unusual. Actually, case in point, two elements of familiarity joined in unusual ways also creates that “strange.” Like the cowboy-vampire-princess story earlier.

And finally, stories with a premise so out-there and characters so rarely seen that the reader has to be willing to put a lot of trust in the writer to understand them. These stories are often experimental and out-there. A well-done book of this variety often receives a lot of acclaim but also a lot of readers bouncing off of it like they hit a brick wall. In the analogy, it’s like being stranded in the middle of the ocean and the person who discovers you is your teacher who’s out on their first solo flight in a Blackbird or something. So far outside your familiar realm that it strains credulity. Such a book is going to be controversial at first. But then…

Here’s an interesting part of this. The longer a story element is around, the more familiar it becomes. Frankenstein was groundbreaking when Mary Shelley wrote it; now it’s a cliche. The same has happened to Dracula, Lord of the Rings, and many other classics that were in the third category when they were written. Over time, they slide up the familiarity scale/down the strangeness scale until they’re part of the everyday parlance of the reading world and it can be hard for us to see what was so strange about them when they first came out.

Again, this is good as a tool for analysis and audience engagement, and maybe as a tool for figuring out what’s going on if you’re turning a lot of beta readers away from your book, but it’s not a measure of a book’s worth. That comes in what it does for the people reading it. If they come away having enjoyed their time and it hasn’t made them worse people as a result, it’s a good book. (If they come away better and more empathetic, then it’s a great book. But that’s a topic for another day.)

Intellectual Property of Elizabeth Doman

Feel free to share via link

Do not copy to other websites or skim for AI training